What is POTS?

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome is a disorder of the autonomic nervous system. It affects heart rate, blood vessel dilation, blood pooling, movement of food through the digestive system, and body temperature.

POTS falls under the more general umbrella of disorders called dysautonomia. POTS, like all dysautonomias, is characterized by dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system which controls many “automatic” physiological functions including blood pressure, heart rate, blood vessel and pupil diameter, movements of the digestive tract, and body temperature. In dysautonomia, the person can suffer from a wide range of symptoms that are ultimately connected by the dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system.

One of the hallmark symptoms of POTS is orthostatic intolerance which results in increased symptoms when upright. Because the autonomic nervous system is not functioning correctly, the constriction of blood vessels that normally occurs when we transition from sitting to standing is decreased or absent. This lack of vessel constriction leads to blood pooling in the legs and abdomen, which results in a shortage of blood in the heart and brain. The shortage of blood in the brain upon standing can result in dizziness, light-headedness, and possibly fainting (Mayo Clinic) Because of this, it is important for an individual with POTS to sit on the edge of the bed or recliner for 10-15 seconds before standing to give the body time to respond to the change in position.

Quality of Life with POTS

Developing POTS is a game changer for that person and their family. While it is a chronic invisible illness and the person "looks fine" on the outside, the symptoms experienced by that individual are often debilitating and life altering. A person with POTS uses three times more energy to stand than normal. Even minor movements around the house, including eating meals and showering, can be exhausting and increase symptoms (Grubb et al. 2006). The quality of life of a person with POTS has been compared to those with congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; Benrud-Larson et al. 2002). POTS can truly be debilitating.

Demographics

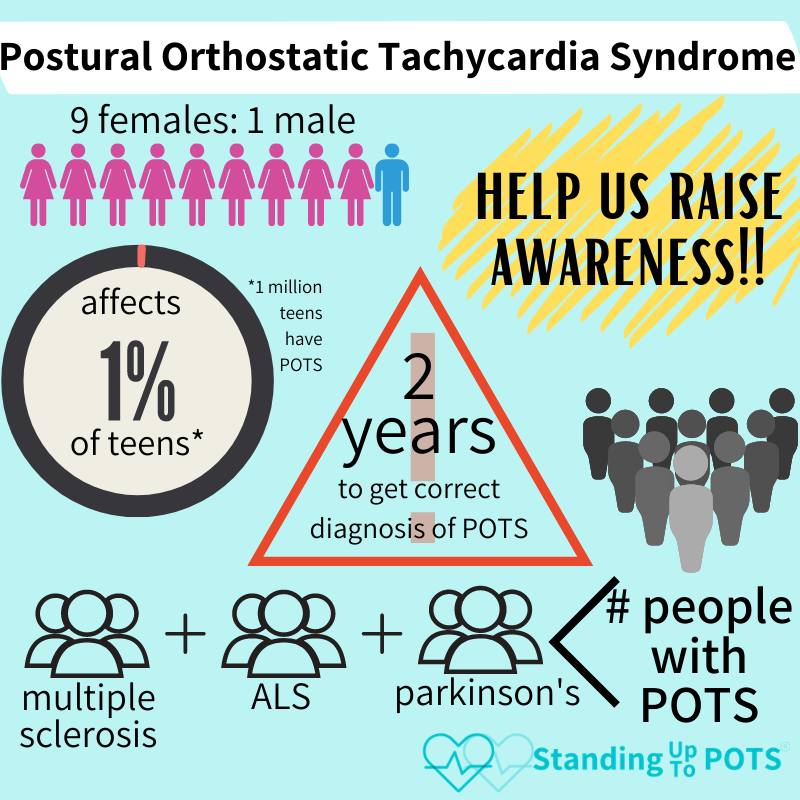

While anyone can develop POTS, approximately 75% of those diagnosed are women between the ages of 15 and 50 (NIH.gov). POTS can be triggered by a variety of life stressors including pregnancy, major surgery, trauma, or a viral infection like mononucleosis, Lyme disease, or COVID (NIH.gov). The question is why POTS occurs in only a few women who start families, have mono, or get in a car accident. Unfortunately, there is no answer to that question at present.

POTS is not a rare disorder (rare is defined as less than 200,000 people in the US with that diagnosis). Pre-COVID, the estimate in the US is that 170/100,000 in the general population have POTS (Low et al. 2009), about 540,000 Americans. It is suspected that 1/100 teenagers in the US have POTS. Some people develop POTS secondary to another disorder like diabetes, amyloidosis, heavy metal poisoning, Sjogren syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, or paraneoplastic syndrome (Agarwal et al. 2007).

Prognosis

The long-term prognosis varies based on the underlying cause and overall severity of symptoms. A study of 121 pediatric POTS patients over time found cumulative symptom-free rate gradually increased over time, especially if the illness was diagnosed early and proper treatment was initiated quickly (Tao et al. 2019). However, POTS does not simply disappear, and most teens don’t outgrow this disorder. In fact, only 20% of teens made a full recovery within 10 years. Only 50% of people who develop POTS after a viral infection recover in five years, while those with primary hyperadrenergic form will require lifelong treatment (Agarwal et al. 2007).

A study of 42 adult POTS patients found significant improvement in symptom burden and quality of life after 2 years of treatment, but the symptom burden was still high and did not improve occupational status (Dipaola et al. 2020).

In a mailed follow-up study of POTS patients, with only a 34% response rate (may be skewed toward positive outcomes), the prognosis for pediatric POTS cases was found to be:

- 33% of pediatric patients had complete resolution of symptoms after 5 years

- 51% reported persistent but improved symptoms

- 16% reported intermittent symptoms

- 71% considered their health to be at least “good.” (Bhatia et al. 2016)

For individuals with POTS secondary to another illness, treatment of the underlying disorder (Addison’s disease, Crohn’s disease, mast cell activation syndrome, etc.) is critical in order to control POTS symptoms. Compassionate continuing care is critical to achieve a decent quality of life for these chronically ill patients.

Check out these POTScast Basics Episodes with Dr. Cathy Pederson

POTScast, Episode 1: What is POTS

POTScast, Episode 4: Autonomic Nervous System 101