What should POTS patients and/or providers know about Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS)?

There is an important link between antiphospholipid syndrome (also known as Hughes syndrome or “sticky blood”) and dysautonomia that is poorly recognized. This association was first published in early 2014 [1] and is important to recognize because left untreated it may cause severe disability. When the correct diagnosis is made, however, there are often effective treatments, including treatments for sticky blood and treatments that target the immune system.

Antiphospholipid syndrome is a complex autoimmune clotting disorder characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL). The hallmarks of antiphospholipid syndrome are arterial or venous blood clots, including stroke, heart attack, pulmonary embolus, or deep vein thrombosis and pregnancy complications, including recurrent miscarriage, stillbirth and pre-eclampsia. I believe antiphospholipid syndrome will come to be recognized as a not infrequent association with POTS, but there has not yet been a study looking at the frequency of aPL in POTS so we don’t currently know what percentage of patients with POTS might have aPL.

A major problem with this association is that the current Sydney classification criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome were intended to capture a uniform population of patients for research purposes focusing on blood clots and serious pregnancy problems. As a result, the criteria require a blood clot or serious pregnancy complication to make the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome. There are other important clinical manifestations that occur in patients with aPL, however, including many neurological manifestations such as POTS that are not included in the criteria. In addition, these research criteria were never intended to be used for diagnosis but they are because diagnostic criteria do not exist. The result is that POTS patients who have one or more aPL are often not taken seriously until or unless they have had a clotting event--which can be severely disabling or even fatal! The other problem with the Sydney criteria is that they require a moderate to high titer aPL—higher than the cut offs set by the scientists who developed the assays—for a patient to qualify for a diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome. In general the higher the aPL titer, the higher the clotting risk, but individual patients may have very disabling complications of aPL despite low titers. In fact, some of my sickest patients have only low titer aPL.

I consider the persistent presence of even a single and low titer antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) as an important risk factor for clotting or pregnancy complications in my patients with POTS and when persistently present I presume these antibodies are involved in the pathogenesis of the patient’s POTS. This is because it has been shown that patients with POTS and aPL have autonomic neuropathy when skin biopsy is performed [2] and severely affected patients have a high likelihood of responding to intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) [3].

Additionally, the majority of patients with aPL and severe migraine and/or memory loss notice a significant improvement in or even resolution of these symptoms with a trial of antithrombotic therapy—either anti-platelet agents (aspirin or clopidogrel) and/or anticoagulation. These medications make the blood less sticky [4]. The hypothesis is that these manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome occur due to sludging of the blood and, much like running old oil through your car, your brain does not work as well when the blood is sticky.

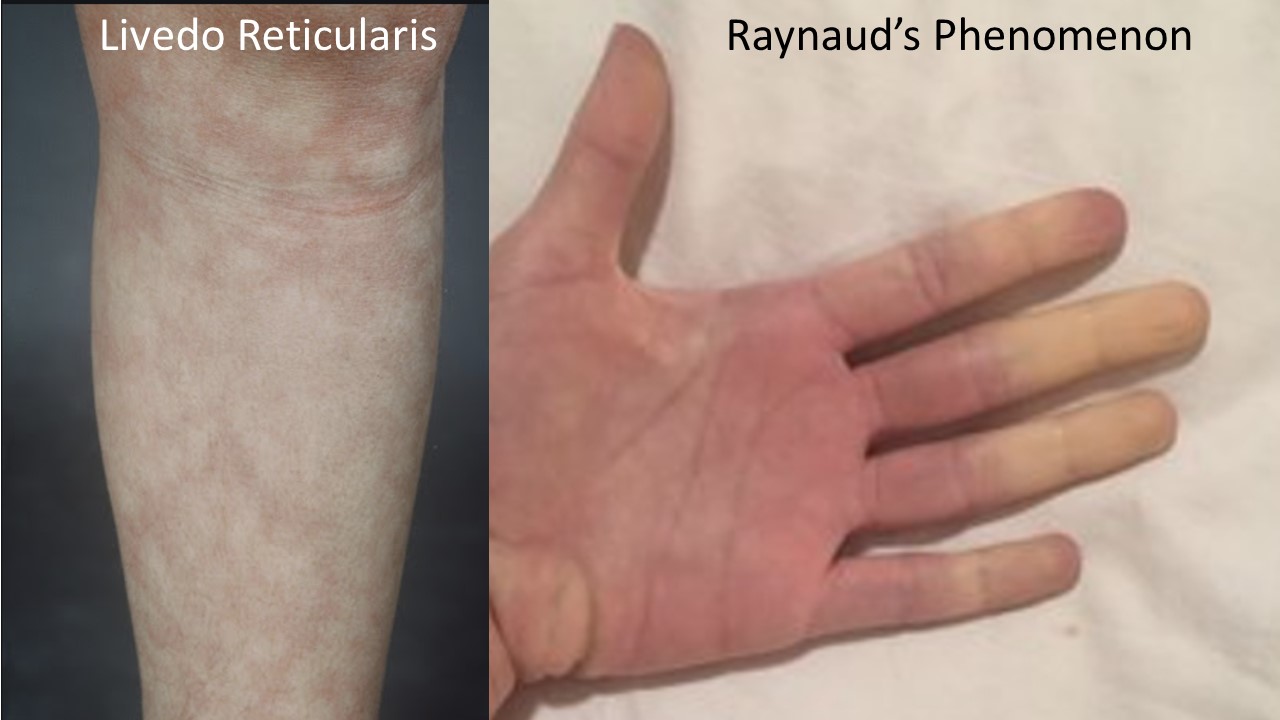

There is a characteristic clinical phenotype of dysautonomia patients more likely to have aPL. This includes frequent migraine (which often begins in elementary or middle school but becomes more severe with the onset of POTS and is often but not always associated with aura), prominent memory loss which many patients can distinguish from the brain fog of POTS as more blank spells and word finding issues than globally slowed or foggy thinking. Many patients have livedo reticularis (see photo) which is a mottled or lacy pattern on the skin (usually on the arms and legs) that may be more prominent in the cold or when getting out of the shower. Patients may also have Raynaud’s phenomenon in which the fingers and/or toes turn color (and often numb) in response to the cold, low platelets, low or low normal white blood count, white matter change on brain MRI, unexplained stress fractures or thickening of their heart valves. It has also been my strong anecdotal experience that patients with very hyperadrenergic POTS (with severe labile hypertension, very low blood volume and severe tachycardia) often have aPL. If you have one or more of these clinical features in addition to POTS, it is appropriate to be tested for aPL.

I recommend testing for the aPL included in the Sydney criteria (“criteria aPL”) as well as for the available “non-criteria aPL” that have become associated with antiphospholipid syndrome since the Sydney criteria were published (initially in 1999 and revised in 2006). This is because it has been shown in a large study of obstetric patients with aPL that patients with non-criteria aPL and non-criteria clinical manifestations responded similarly to treatment [5]. We found the same results in our patients with aPL and refractory migraine [4].

Criteria aPL include:

- Anticardiolipin IgG, IgM

- Anti-beta 2 glycoprotein IgG, IgM

- Lupus anticoagulant

Non-criteria aPL include:

- Anticardiolipin IgA

- Anti-beta 2 glycoprotein IgA

- Anti-phosphatidylserine IgG, IgM, IgA

- Anti-prothrombin IgG (IgM is not currently available due to reagent shortage; this has been the case for a few years)

- Anti-phosphatidylserine-prothrombin (PS-PT) IgG, IgM

- Anti-Annexin V IgG, IgM

- Anti-phosphatidylethanolamine IgG, IgM

- Anti-phosphatidylcholine IgG, IgM

Some patients have several aPL while others have only one. It is recommended to confirm persistent positivity by repeating the aPL testing in 12 or more weeks. I consider the persistent positivity of even a single low titer aPL to be important in a patient with clinical problems that have been described in association with these antibodies, including POTS.

The treatment depends on the patient’s clinical situation, but might include consideration of a trial of antithrombotic therapy and consideration of a trial of immune modulatory treatment such as IVIG in severely affected patients and/or hydroxychloroquine in less severely affected patients. It is also important to recognize the increased clotting and pregnancy risk present in these patients in the hopes of preventing these serious complications.

It is my hope that with time, there will be increasing awareness about this important association.

REFERENCES:

- Schofield JR, Blitshteyn S, Shoenfeld Y, Hughes GRV. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other autonomic disorders in antiphospholipid (Hughes) syndrome (APS). Lupus. 2014; 23: 697-702.

- Schofield JR. Autoimmune autonomic neuropathy—in its many guises-- as the initial manifestation of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Immunol Res. 2017 Jan 24; 1-11.

- Schofield JR, Chemali KR. The efficacy and safety of intravenous immunoglobulin in severe autoimmune dysautonomias: a retrospective analysis of 38 patients. Am J Ther. 2018 May 14. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000778. [Epub ahead of print]

- Schofield JR, Birlea M, Hughes H, Hassell KL. Refractory migraine: when is a trial of antithrombotic therapy appropriate? Submitted for publication.

- Alijotas-Reig J, Esteve-Valverde E, Ferrer-Oliveras R, Sa´ez-Comet L, Lefkou E, Arsene Mekinian A, et. al. Comparative study of obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome (OAPS) and non-criteria obstetric APS (NC-OAPS): report of 1640 cases from the EUROAPS registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019 Oct 3. pii: kez419. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez419.